The Arrusi and the Policing of Gender and Sexuality in Fascist Italy

by Dr. Alessio Ponzio

Fascist Pronatalism

During the Fascist regime (1922–1943), Benito Mussolini presented himself as the leader who would transform Italian society, turning Italian men and women into devout Fascists.

Benito Mussolini (1883-1945)

Benito Mussolini (1883-1945)

Men were expected to embody the values of the fighting husband and father, and women were expected to become wives and mothers of the new citizen-soldiers. The new Italian man and woman would be created through a totalitarian educational plan carried out by the regime's organizations. A primary goal of the Fascist project was to increase the Italian population. The Fascists believed that a nation's power depended on its numbers, and Mussolini wanted to increase the number of inhabitants on the peninsula. Fathers were given preference when hiring new workers, and women's work and emancipation were discouraged so women could focus on their role as mothers.

The regime wanted to increase the number of marriages in the country and encourage men to marry at a young age. To this end, the Italian state introduced a tax on bachelors in 1927. Unmarried men between the ages of 25 and 65—with a few exceptions, such as war invalids and Catholic priests—were required to pay the tax. Men were exempted from payment upon reaching the age of 66. In addition to the basic tax, which was calculated according to age brackets, there was an additional income-based rate.

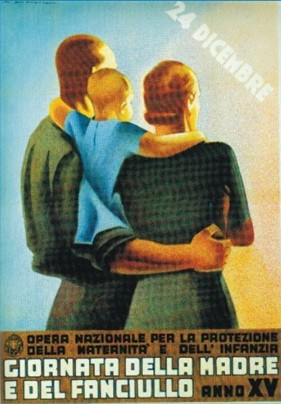

The money collected through this tax was allocated to the National Maternity and Infancy Organization (Opera Nazionale Maternità e Infanzia - ONMI). Established by the regime in 1925 and dissolved in 1975, this state agency aimed to assist mothers, girls, and children in need; address pregnancy-related mortality; and manage the abandonment of newborns. ONMI staff included pediatricians, gynecologists, obstetricians, child psychiatrists, and general practitioners. The ONMI aimed to promote reproduction and motherhood by fighting against abortion and contraception.

Poster from OMNI celebrating Mother and Child Day (December 24) - 15th Year of the Fascist Era (1937)

Poster from OMNI celebrating Mother and Child Day (December 24) - 15th Year of the Fascist Era (1937)

To encourage Italian couples to have children, the fascist regime offered financial aid and bonuses for large families. However, Italian fascism sought to increase the population through other means as well. Starting in 1926, the use of contraceptives was banned in the country. Then, in 1931, the penal code began to provide for heavy prison sentences for aiding, abetting, procuring, or performing abortions.

Despite these efforts, the pro-natalism campaign produced results that were far below expectations. Many women, including those in rural areas and the urban middle class, managed their fertility through withdrawal and clandestine abortions. Thus, Italian women showed a certain resistance to policies that sought to control their bodies and personal choices.

Decriminalization of Homosexuality in Italy

To the fascists, homosexuals were enemies of the system and of the "new man" desired by the regime. They could not be tolerated because, allegedly, they undermined Mussolini's political project. The regime claimed that homosexuals were dangerous to the younger generation because they corrupted them and hindered Italian population growth because they refused to participate in the reproductive process. Despite this moral and social condemnation, homosexuality was not officially criminalized in fascist Italy.

Homosexual practices were decriminalized in the Kingdom of Italy at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1791, the French Constituent Assembly promulgated a new penal code that did not mention sodomy as a criminal behavior. In 1810, the Napoleonic Code validated the distinction between law on the one hand and religion and morality on the other, confirming the decision taken by the French revolutionaries twenty years earlier. Sexuality belonged to the private sphere. This principle was adopted by the codes of the Italian states under Napoleonic rule, with two exceptions: Lombardy-Venetia, under Austrian control, and the Kingdom of Sardinia, independent from France. Following Italian unification under the Kingdom of Sardinia, its laws applied to the entire national territory. Among these laws was Article 425 of the Sardinian Code, which imposed severe penalties for any type of unnatural libidinous act.

However, in 1861, a commission of deputies was appointed to extend the Sardinian Penal Code of 1859 to southern Italy. Until then, southern Italy had been a separate state. The commission decided to abolish Article 425 in the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. In this region, sodomy had not been a crime since 1819. This created ambiguity: homosexual relations between consenting adults were punished in the north but legal in the south. The legislative inconsistency between the north and the south was finally resolved in 1889 when the new Zanardelli Penal Code decriminalized homosexual practices throughout the country. The law no longer punished libidinous acts between people of the same sex unless they involved public obscenity or violence. From the late 19th century on, homosexuality in Italy was considered a vice that, when practiced in private between consenting adults, was not a criminal offense.

The Enemy of the 'New Man'

In 1925, when Mussolini decided to revise the Zanardelli Code and introduce a new fascist penal code, the legal status of homosexuality became an issue again. The first draft of the new code, later known as the Rocco Code after Minister of Justice Alfredo Rocco, who was primarily responsible for its creation, criminalized sexual relations between persons of the same sex (according to Article 528). However, the article was removed from the final version in 1931. According to the commission revising the code, a measure for this crime was unnecessary because, "fortunately," the "abominable vice" was not widespread enough to justify legislative intervention. Existing laws would cover crimes such as rape, corruption of minors, assault, abuse, and indecent exposure committed by homosexuals, while the public security laws of 1926 would provide the police with sufficient powers to control the activities of Italian homosexuals.

Despite the Rocco Code's silence on the matter, the fascists could resort to various repressive measures to regulate homosexuality:

- Compulsory confinement in mental hospitals

- Confinement, or exile to small villages in southern Italy or internment in island colonies for renewable periods of one to five years

- Admonition, or probation requiring individuals to observe a curfew, report to the police every morning, and avoid arousing "suspicion"

- Warning, or notification that an individual was under observation.

The fascist administration did not need evidence to send someone into confinement. These were extrajudicial measures imposed by the police, so there were no trials, and these men had no chance to defend themselves.

The Italian fascists wanted homosexuals to keep their condition secret. Thus, mental hospitals, confinement, warnings, and admonitions became the preferred methods of punishing these individuals while avoiding "dangerous" and "unnecessary" publicity. The regime covertly censored homosexuality, isolating or threatening homosexuals. "Homosexual vice" was unspeakable and had to remain so.

Fascists were particularly interested in censoring and repressing effeminacy and gender nonconformity. They punished the outward absence of masculinity more than homosexual behavior itself. In fascist Italy, effeminate men, whether or not they were homosexual, were despised and ridiculed because they were the antithesis of the fascist "new man." Men who engaged in homosexual relationships without causing scandal had a chance of living their sexuality without encountering fascist repression. However, homosexuals who displayed effeminate behavior (often called pederasts by the fascists) were more likely to be subject to psychiatric and police repression.

If approved, Article 528 would have punished men and women who committed "acts of lust with persons of the same sex." However, in the end, only visibly homosexual men were punished in fascist Italy. Like Nazi Germany, Italy did not specifically target lesbians, although they could be punished using other regulatory instruments. Female sexuality was denied, and the silence surrounding lesbian love and behavior was a clear sign of this denial.

The Power of Silence

Unlike in Nazi Germany, where homosexuality was codified in law and punished by Paragraphs 175 and 175a and publicly condemned, homosexuality was not written into statute in Fascist Italy; but neither was it openly discussed. For the fascists, silence was the best way to combat homosexuality. Discussing homosexuality could have led to a discourse that would stimulate curiosity and make the "vice" more visible.

Since January 1926, Mussolini had argued that the nation would be reformed through the moralization of the press and strict censorship of "vice" and "perversion." The Fascists dismantled crime reporting, arguing that sensationalism hindered the emergence of a positive image of the new Italian state. Therefore, the regime indicated all crimes that could not be publicized by the media. This list included crimes against public morality and decency, as well as crimes against the family, the integrity of the race, and the health of the race. Newspapers could not report on scandalous events or mention "pederasty," infanticide, or sexual "vices." The press could not report on tragic acts of passion or gruesome news stories. Even advertisements had to follow these rules. Medications or treatments for sexual dysfunctions, such as impotence, could not be advertised in the Italian media. Representations of homosexuality and crime could not appear in Italian contexts. "Vices" and "perversions" could only be depicted if they took place in other countries or distant, "exotic" lands.

The fascists also censored encyclopedias and magazines dedicated to the study of sexuality. Aldo Mieli, a science historian and socialist, had been interested in sexuality and sexology since the early 1920s. In 1921, he founded the Italian Society for the Study of Sexual Issues, as well as Rassegna di Studi Sessuali (Review of Sexual Studies). This journal published articles on sex and sexuality by foreign sexologists. Mieli sought to encourage public debate on sexual issues, presenting homosexuality as natural behavior rather than a pathology. Because of his scientific work, activism in sexology, and political views, Mieli was forced to leave Italy in 1928.

Fascist Italy sought to dictate rules regarding gender roles and sexuality. The regime was particularly obsessed with protecting the youth from "deviance" and attempted to create new Fascist men and women through youth organizations, with debatable success. The regime waged its demographic battle by criminalizing contraceptives, abortion, and interracial relationships and by fighting pornography and homosexuality. Fascists supported male sexuality, especially reproductive sexuality, and also favored access to female bodies by regulating prostitution in officially recognized "brothels." For fascism, sexuality was an essential political tool for guaranteeing and increasing the power of the state. Despite the repression, however, many resisted the regime's plans. There were men and women—homosexuals and heterosexuals alike—who managed to find spaces where they could live according to their desires, feelings, and emotions.

Arrusi

On February 2, 1938, the new police commissioner took office in Catania. Police Chief Alfonso Molina was a loyal regime official. He had already distinguished himself in Salerno and Avellino with his obsession to repress homosexuality.

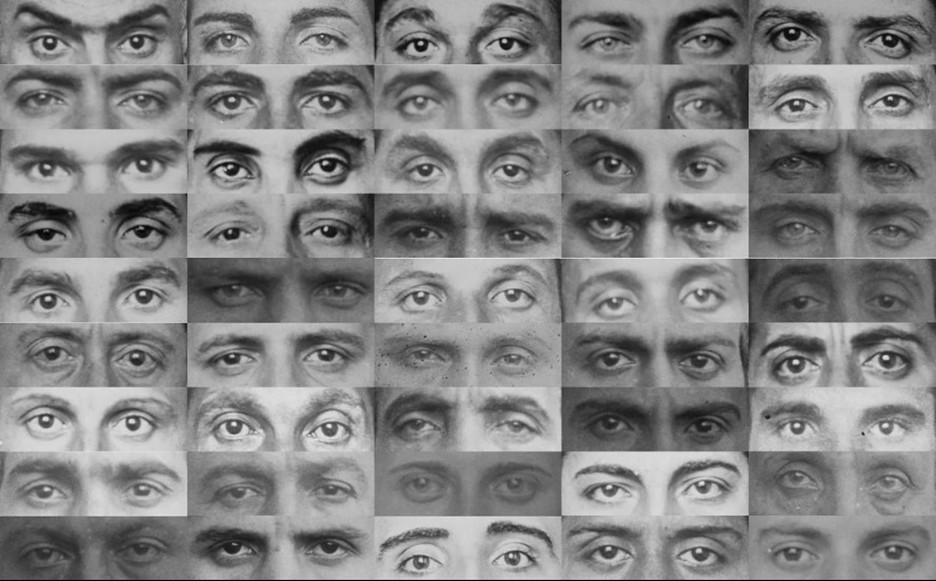

Following an unsolved murder in Catania's homosexual scene, Molina decided to crack down on the city's homosexuals. In early 1939, under Molina's orders, the police rounded up 45 gay men — residents of Catania and some small towns in the province. Accused of "passive pederasty," the men, ranging in age from 18 to 54, were forcibly removed from their homes and communities. They were subjected to invasive medical exams and confined to the Island of San Domino, located off the coast of Apulia.

The forty-five men from Catania who were sent to San Domino were called arrusi because they were accused of being passive pederasts—men who took on a passive role during male-to-male sexual encounters.

The word arruso, which is also found in Calabrian and Sicilian as garruso or jarruso, comes from the Arabic arùs, which means "bride."

The arrusi from Catania were released in 1940, but they remained under surveillance for two years. They were released only because the regime needed the island to imprison political enemies when Italy entered World War II. Historians Gianfranco Goretti and Tommaso Giartosio reconstructed their story, and photographer Luana Rigolli put faces to their names.

The arrusi of Catania were not the only homosexuals sent to confino. Other homosexuals were sent to different islands – such as Ustica - and isolated towns in the Italian south.

Lucania (or Basilica in red)

Lucania (or Basilica in red)

For example, Cristoforo Magistro recounted the stories of men exiled in Lucania, another southern Italian region, in his photographic book Adelmo e gli altri (Adelmo and the Others).

Stories about men who were sent to confino because of their homosexuality have been fictionalized in movies (A Special Day, 1977), comic books (In Italia sono tutti maschi - In Italy there are only real men, 2008), and novels (Mussolini’s Island by Sarah Day, 2017; L’isola dei femminielli – The Island of the Femminielli by Aldo Simeone, 2024).

The Letters

Luana Rigolli photographed the arrusi and the documents preserved in their personal files. In her photobook, she publishes one document for each person sent into confinement. Some were written by the arrusi themselves, some by their families, and some by police chief Alfonso Molina, who sent them away from Catania.

Taken together, the letters written by the arrusi do not portray them as dangers to society, but rather as respectable, suffering, and redeemable individuals. Each confined man emphasizes his normality and usefulness as a worker, son, soldier, father, or artist, while stressing his loyalty to fascism, devotion to family, and willingness to serve the nation. They invoke illness, youth, poverty, and past abuse to frame their alleged "crime" as a misunderstanding, a youthful mistake, or the result of others' deceit. The tone is humble and deferential, addressing the state as a paternal authority capable of mercy. Different voices use the same rhetorical strategies: appeals to respectability, claims of innocence or reform, and careful alignment with Fascist ideals.

In letters from their families, the arrusi are shown not as criminals but as good, hardworking men who matter to their families and to the nation. They are described as workers, soldiers, sons, and breadwinners—young men whose honesty and usefulness are stressed to fight the shame of arrest. Most letters come from parents, siblings, and even a child, and they present these men as victims. The writers often mention illness, poverty, youth, and past suffering to ask for sympathy and to suggest the charges were mistakes. At the same time, they strongly support fascist values, praising Mussolini, the monarchy, discipline, and service to the country. Overall, the letters show that to survive under repression, families had to present these men as loyal, moral, and deserving of pity—not as enemies of the system, but as people who should be forgiven, not punished.

In his letters to the central government, Police Chief Molina views each man through a rigid, moralizing lens. He treats homosexuality not as an identity, but as a vice, a disease, and a threat to public order. He consistently pathologizes individuals as "degenerate" or "perverted," criminalizes them by linking sexuality to theft, idleness, and the corruption of youth, and medicalizes them through the language of examinations, infections, and "unnatural" acts. Molina portrays homosexuality as a social danger rather than a private matter and repeatedly depicts these men as initiators who "corrupt" or "infect" others, especially the young. He equates homosexuality with pedophilia and considers these individuals to be guilty, even without a proper trial. By blending police authority, pseudoscience, and fascist moral ideology, Molina's writing does not seek to understand individuals, but rather to categorize people as inherently dangerous, incorrigible, and deserving of removal from society through confinement. Molina wants to dehumanize these individuals in the eyes of the central government, so these letters should be considered in that context.

The arrusi, simply by looking at us, force us to reckon with the cruelty of political, social, and cultural systems that deny people the right to live as their true selves. Their faces and eyes linger with us, quietly asking why governments around the world still punish and discriminate against queer people who are only trying to exist.

Reception and Panel Discussion

Join us on March 9th to celebrate the launch of “Faces of Exile: The Arrusi and the Policing of Gender and Sexuality in Fascist Italy” photographic exhibition.

Meet the artist, enjoy refreshments, and engage in conversations about power, persecution, and the institutional policing of sex, sexuality, and gender.

The event is free, but please register for catering and set-up purposes.